@back2dos Thanks for the kind words! Your points are well reasoned, I think it is indeed paradoxically less ambitious. Though go2hx already use’s Go’s frontend, building a Go backend first to bootstrap go2hx later on, has a number of benefits you’ve rightly pointed out. In addition here are some that come to mind for both unambitious projects (would love to hear any others ideas that come to mind!):

- A Go target forces a solution to Go and Haxe interoperability/externs early on, that can be standardized in both directions.

- Transforming Haxe syntax and Haxe’s stdlib to Go code is substantially easier then the reverse.

- go2hx v2 @back2dos “start with generating externs, later generate code.”

- go2hx v2 run on the Go target to be able to interface directly with the Go compiler tooling from the start.

- go2hx v2 can compile Go → Haxe on the Go target to test the compiler without imports, by bypassing them (useful for language only specification compliance).

- go2hx v2 significantly less complex and written 100% in Haxe.

- An additional backend :] with a state of the art gc, cross compiling, single executable binary, and fast build + run times!

- Build again with a team from the start, and with maximum nerd sniping efficiency along the way! Open source, easy to collaborate on, with lots of delicious dog food to eat!

Research paper review

I also decided to write a review today on a research paper done by Yeaseen Arafat from the university of Utah. The work evaluated go2hx (and other compilers) with a new state of the art general purpose transpiler fuzzer, TeTRIS!

PDF of paper

Reported go2hx bugs

I’m very happy that a project we’ve passionately worked on for so long, is included in cutting edge research and directly benefiting from it. I have a lot of respect for Yaseen and sincerely believe a feedback loop of compiler dev teams using + giving feedback / contributing to improve the next generation fuzzers will advance the field tremendously.

The review format is, I took screenshot snippets of the paper and will give commentary under them. A conclusion is written at the end.

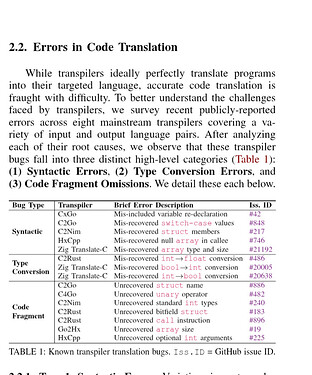

This is such a clever way to categorize the errors found in transpilers. It would be fascinating to observe what the percentage of each category of errors is, as a compiler matures.

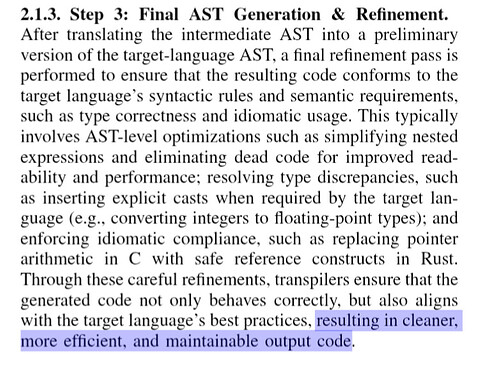

This is the most ideal scenario. For most transpilers reaching correctness on the specification is not completed. A non toy compiler has to be correct above everything else, and often times many trade offs need to be made that prevent a compiler from being better then the input language in any of those parameters. Take for example hxcpp, the Haxe → C++ code produced by the compiler is not more efficient, maintainable or cleaner then hand written C++, but it is still an extremely valuable compiler because it is highly correct in it’s transpilation and is often times only slightly less efficient. The maintainability and cleanliness more often then not comes from the compiler it’s self being easy to reason about and being able to trace back to the source code from the generated code.

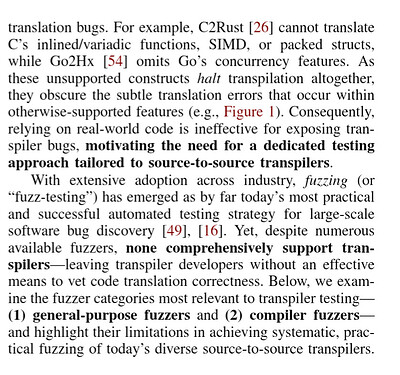

This is a fantastic point, and more to the point, for the development of compilers, it is vital to iterate on the supported sub-specification (research paper on it) for the smoothest development experience. This approach allows the compiler to be worked on systematically rather then by a random patching methods, that often times leaves systems almost working, causing cascading issues, that are hard to reason about, slowing development to a crawl.

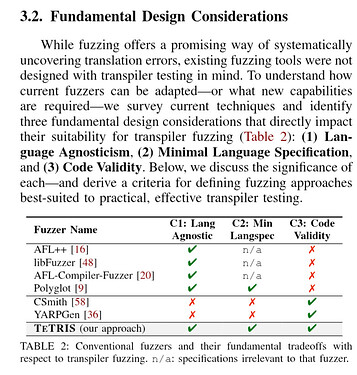

Great way to frame why TeTRIS is so useful in it’s approach, in particular setting a minimum language specification is so incredibly useful for compiler writers, amazing insight!

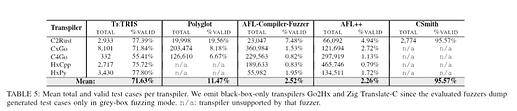

I was expecting above 90% validity for TeTRIS, would’ve been nice to get the details on why the Haxe generation is around ~75% and how it could be improved. Haxe is probably one of the best languages to run the fuzzer on, because it can be used to compare all of it’s backends which could likely use a lot of help finding corner case bugs and defining the undefined behavior regions across targets.

I mention this because, if I’m not mistaken, CSmith did the same thing with clang and gcc to perform differential testing. In my view this is a very under tapped field of research.

Conclusion

I’m sold on the idea conceptually, that TeTRIS should be one of the key tools used when designing source to source compilers. Given the alternatives and many of the exclusions of other fuzzers that were made because of language/feature limitations, it’s clear that this is a novel approach that has the potential to not just advance research but also bring about more mature transpilers in a shorter time frame. I could also see it or a future iteration, being the premier tool to use when developing a Haxe backend or transpiler into Haxe. I hope that the momentum continues and that TeTRIS blossoms into a useful and community driven open source project.